Empowering Women in Higher Education Leadership

Though men still hold the majority of executive leadership positions in higher education, women represent more than half of administrators overall, according to a study from the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources (CUPA-HR). Women in higher education leadership bring unique skills to bear on their approach to leading — skills honed by navigating the competing demands of their gender and their occupation.

Women in Higher Education: Stats and Trends

The number of women in higher education leadership is on the rise, but that is a relatively recent development. In the not-so-distant past, women couldn’t attend most colleges and universities in the U.S., much less dream of leading them. Higher education has come a long way since then, but it still has some miles to travel on the road toward gender parity.

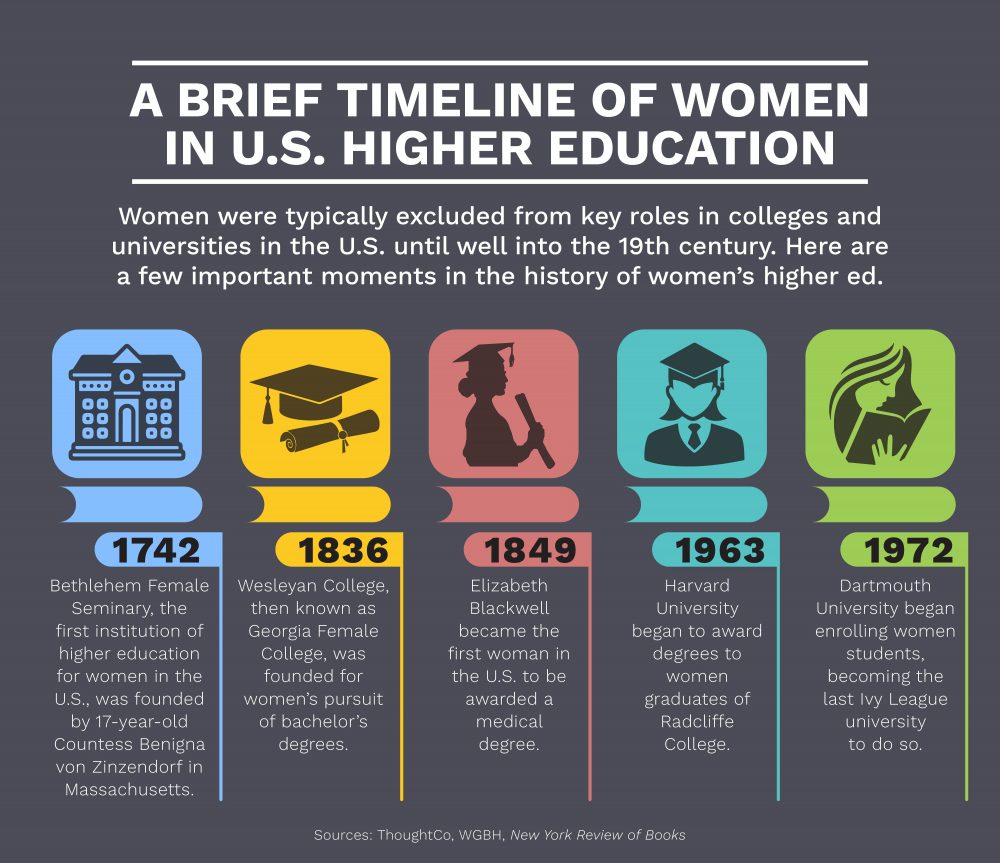

Women’s Journey Through U.S. Higher Education

The first universities in the U.S. largely barred women from attending, and those women who were able to secure an exception were typically wealthy and white. In the early 18th century, women began to establish their own private institutions of higher education, though the attendees remained of the same class and racial background.

The passage of the first These colleges welcomed women from their inception due to the reduced cost of operating one coed school as compared to two sex-segregated institutions. Private Ivy League schools such as Harvard and its sister college Radcliffe soon followed, though many schools operated on a sex-segregated basis. By 1869, 14.7% of bachelor’s degree recipients in the U.S. were women, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

Since 1982, women overall have outperformed men in earning bachelor’s degrees, and are more likely than men to finish college by age 31. In the 2017-2018 academic year, 57.3% of bachelor’s recipients overall were women, and the outperformance is particularly evident among Black and Latina women, according to the NCES. White men still outpaced white women as bachelor’s recipients, with 65.2% of graduating men being white compared to 61.7% of graduating women. Asian/Pacific Islander men also outpaced Asian/Pacific Islander women, with 8.6% of male graduates being Asian/Pacific Islander compared to 7.6% of graduating women.

Of all women in higher education, bachelor’s degree recipients in the 2017-18 academic year broke down like this:

- 9% were Latinas, compared to Latinos at 13.2% of graduating men

- 4% were Black, compared to Black men at 8.9%

- 5% were Native American, compared to Native American men at 0.4%

A History of Female Leaders in Higher Ed

Historically, dean of women was one of the few top leadership positions available to women. that started admitting women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these administrators were tasked with safeguarding the purity of their young charges and guiding their academic progress. Institutions recruited women faculty members for the role, one primarily created due to the distaste of men in leadership positions for dealing with “women’s business.”

Women’s representation in higher education leadership increased as more women graduated from college. Out of 5,553 total professional jobs available in higher education during the 1969-70 academic year, women held just 11.9%. Twenty years later, in the 1989-90 academic year, the total jobs available had increased dramatically to 1.5 million, and women held 42.4% of them. However, significant gaps still exist between white women and women of other racial and ethnic groups.

Women in Higher Education Leadership Today

Gender inequalities in the workplace remain at the top levels of higher education leadership, even for white women. Overall, women’s gains have been disproportionately spread among certain areas of employment on campus, such as academic affairs, fiscal affairs, and student affairs, according to data from CUPA-HR. Women make up 69%, 71%, and 66% of leaders in these areas, respectively. In other areas, such as facilities, information technology, and athletics, women trail by large percentages. They make up just 19%, 28%, and 29% of leaders in these areas.

Representation is sparse for Black women and other women of ethnic and racial minority groups. Black women and Latinas make up a combined 9% of leaders in academic affairs, 2% in athletics, 3% in facilities, 14% in student affairs, and 3% in information technology. At 17% Black/Latina representation, fiscal affairs is the most diverse area of employment when it comes to leadership roles. Clearly, more effort must be put toward advancing Black, Indigenous, and other women of color to executive leadership positions in all areas of higher education.

Data on LGBTQIA+ women in higher education leadership is even more sparse than their numbers. Reliable statistics are difficult to come by. One organization, LGBTQ Presidents in Higher Education, claims 80 members among its ranks. How many of those members are women is unclear.

Women were typically excluded from key roles in colleges and universities in the U.S. until well into the 19th century. Here are a few important moments in the history of women’s higher ed. 1742: Bethlehem Female Seminary, the first institution of higher education for women in the U.S., was founded by 17-year-old Countess Benigna von Zinzendorf in Massachusetts; 1836: Wesleyan College, then known as Georgia Female College, was founded for women’s pursuit of bachelor’s degrees; 1849: Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in the U.S. to be awarded a medical degree; 1963: Harvard University began to award degrees to female graduates of Radcliffe College; 1972: Dartmouth University began enrolling women students, becoming the last Ivy League university to do so.

Barriers for Women in Higher Education Leadership

Making it to the top of the higher education leadership heap as a woman can mean doing more work for a fraction of the pay. For women of color, queer and trans women, and women who inhabit multiple marginalized identities, the labor demanded is even more intensive. Sexism and misogyny, racism, and a workplace culture hostile to family commitments are just a few of the structural barriers that aspiring female leaders in higher education face.

Women in Higher Education Leadership: Challenges and Triumphs

Higher education’s history of excluding women contributes to the lack of diversity in its upper echelons of leadership, particularly at elite institutions. Women who aspire to leadership roles in higher education must overcome obstacles such as gender stereotypes, institutional biases, and a lack of administrative support. According to Maryville University’s Associate Professor of Higher Education Leadership Susan Bartel, “insidious influences and unconscious bias remain in place for the majority of would-be women leaders in higher education.”

The typical path for academic career advancement does not allow for responsibilities such as child rearing or caring for elderly family members, which disadvantages women at greater rates than men. And compared to men, women are more likely to be assigned and to take on service work such as advising and sitting on committees. According to Bartel, “Colleges and universities often do this as part of an effort to correct a gender imbalance in institutional leadership, which in itself is a positive goal; however, these tasks do not necessarily lead to the same kind of career advancement opportunities as the more highly valued and rewarded activities like scholarship or leadership initiatives do.”

Much progress is yet to be made — for example, women in higher education leadership roles earn on average 80% of what men in the same positions earn, according to CUPA-HR — but women have overcome enormous obstacles to reach their current level of representation in higher education leadership.

Higher Education Leadership Skills

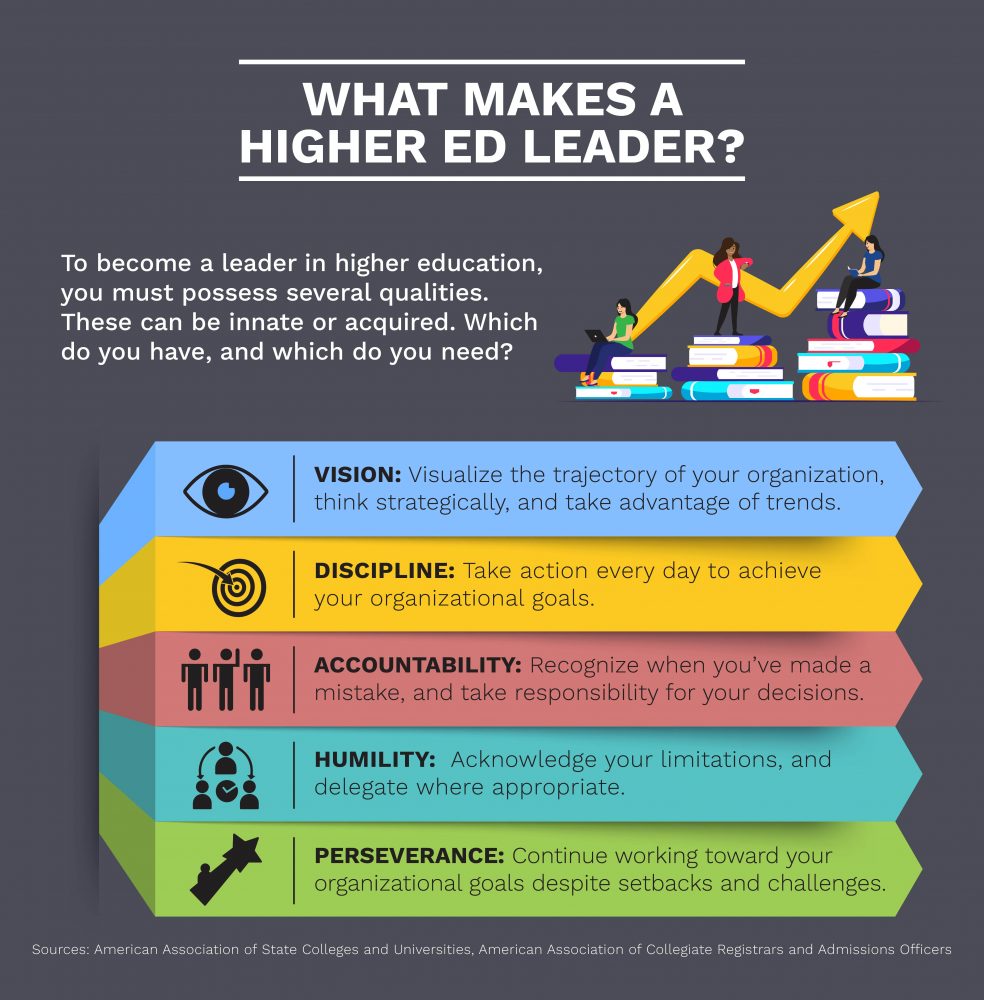

Aspiring leaders in higher education should possess or cultivate personal qualities or “soft skills” such as:

- Imagination

- Accountability

- Humility

- Persistence

- Flexibility

Future leaders can develop these skills while pursuing the credentials required for working in higher education. Participating in extracurricular activities such as Rotary Club, volunteering with community organizations, and developing new community programs can provide further opportunities to hone leadership skills.

Most higher education leadership positions require at least a bachelor’s degree, and often a master’s or doctorate for senior roles. Earning a specifically tailored graduate degree, such as a Master or Doctor of Education in Higher Education Leadership, can give graduates an advantage when applying for top positions.

Resources: Common Skills for Leaders in Higher Ed

Learn more about how to develop the skills that higher education leadership positions require.

- Inside Higher Ed, “If You Want to Lead, Start with a Vision” — Learn why a leader’s vision determines the path for their institution’s success.

- TEDxMileHigh, “How to Expand Your Imagination in 8 Days” — Vision requires a strong imagination; nurture it with concrete steps such as daydreaming.

- The Startup, “Success Requires Persistence: A Mini-Guide to Persistence” — Here’s information on the science of persistence and how to build it.

- Psychology Today, “Developing Discipline” — Four simple actions can be taken to improve self-discipline.

- Business News Daily, “Key Steps Women Can Take to Be Strong Leaders” — Here is advice for women on how to excel at leadership.

- Gallup, “5 Ways to Promote Accountability” — Learn about accountability and how leaders can encourage the practice in their organizations.

To become a leader in higher education, you must possess several qualities. These can be innate or acquired. Which do you have, and which do you need? Vision: Visualize the trajectory of your organization, think strategically, and take advantage of trends. Discipline: Take action every day to achieve your organizational goals. Accountability: Recognize when you’ve made a mistake and take responsibility for your decisions. Humility: Acknowledge your limitations and delegate where appropriate. Perseverance: Continue working toward your organizational goals despite setbacks and challenges.

Advancing Women in Leadership: Paths to Senior Roles in Higher Ed

Every leader starts somewhere, and higher education administration offers a number of entry points.

Aspiring female leaders might consider employment areas such as financial aid, student activities, admissions, and academic advising. Ambitious women may find themselves frustrated, however, when it comes to progressing up the career ladder from an entry-level position. In that case, further education or a change of institution may help.

Women are more likely than men to advance to an institution’s presidency from a chief academic officer, provost, or dean position — all jobs that certain entry-level positions can lead to with a little determination.

Entry-Level Positions for Aspiring Leaders in Higher Education

Depending on an institution’s size, some higher ed administrator positions may involve a lot of entry-level work, as well as experience and credentials. The following positions are typically open to recent graduates, with some caveats. All require at least a bachelor’s, while some require a master’s or a doctoral degree to be a competitive candidate.

- Academic support specialist: Works directly with students, linking them with services and advising them on available programs. Can lead to senior roles in student affairs such as assistant director. May require additional certifications such as a teaching credential or counseling license.

- Career counselor: Advises students on post-graduation career paths. Can lead to senior roles in career services such as director of career development.

- Financial aid adviser: Evaluates students’ financial situation and advises on available financial aid packages. Can lead to senior roles in financial aid such as associate director.

Navigating Challenges to Women’s Ambition

Despite the increase of women in administrative roles in higher education, advancing women in leadership will still face challenges in the workplace and at home, often at the cost of their ambition. Many women give up their dreams of attaining senior leadership roles due to the inflexibility of the higher ed workplace culture when it comes to time off for pregnancy and child rearing.

COVID-19 has presented a particular setback to advancing women in leadership, as shuttered schools and stay-at-home policies have forced families to choose between caring for children and earning money. The pandemic has resulted in women leaving the workforce en masse to manage children learning at home or to care for ailing relatives — a choice men are often spared due to the cultural expectation that women will be caregivers.

Profiles of Advancing Women in Leadership: The Upper Echelon

Women in senior administration positions are still too few and far between. Many who do reach the top must carve out a unique path for themselves, dodging the gendered obstacles that can derail careers — but it is possible. Here are some of the women who made it into the upper echelon of higher education leadership.

- Mary Schmidt Campbell, President, Spelman College: Before her tenure as Spelman’s 10th president, Dr. Campbell steered the Studio Museum in Harlem’s path to becoming the nation’s first accredited Black fine arts museum, and served as New York City’s cultural affairs commissioner.

- Amy Gutman, President, University of Pennsylvania: Penn’s president since 2004, in 2022 Dr. Gutman will become its longest serving president since the university’s founding in 1740. Prior to her appointment, she was provost at Princeton University, where she founded the University Center for Human Values.

- Lily D. McNair, President, Tuskegee University: Before her appointment to Tuskegee, Dr. McNair worked as an associate professor, associate director, associate provost and senior vice president for academic affairs, and a provost.

- Janet Napolitano, President, University of California: After serving as governor of Arizona from 2003 to 2009 and as secretary of homeland security in former President Barack Obama’s administration, Napolitano was appointed the first female president of the UC system in 2013.

- Lynnette Zelezny, President, California State University, Bakersfield: Prior to being appointed CSUB’s fifth president in 2018, Dr. Zelezny served as provost and vice president of academic affairs at Fresno State University. Among other roles, she also worked as an associate provost, dean, department chair, and visiting professor at the University of Stockholm in Sweden.

How Universities Promote Gender Equality in the Workplace

Despite gender inequality in higher education’s rocky start, colleges and universities have put in a valiant effort to increase their campuses’ diversity, and in turn increase gender equality in the workplace by producing qualified graduates. Where women were once relegated to separate institutions, now they help to run some of the same schools that excluded them.

From Boys’ Clubs to Inclusive Institutions

When women founded their own colleges, they faced political backlash. Institutions barred instructors from socializing with men, and placed other extreme restrictions on their behavior and appearance. The experience wasn’t much better when women were eventually allowed to attend formerly sex-segregated institutions. Since women were vastly outnumbered, they were uncomfortably visible.

The passage of Title IX — part of a 1972 addendum to the Civil Rights Act that prohibited sex-based discrimination at federally funded academic institutions — resulted in an explosion of coed universities and diversity on campuses. New college affirmative action programs primarily benefited white women, though their eventual dismantling was in part a result of their political characterization as being unfairly advantageous for Black people. Post-affirmative action, higher ed aims to increase enrollment by women and other marginalized groups through a focus on diversity and inclusion.

After years of coeducation, the predominant demographic on college campuses is now white women, and women from all racial groups produce more college graduates than men from their same racial group, with the exception of Asian women. Women as a group have made incredible educational gains since the days of sex-segregated schools, with Black women — once enslaved and outlawed from pursuing education — perhaps coming the furthest of all.

Gender Equality in the Workplace: College Edition

The progress toward gender equality in the workplace overall mirrors the progress toward gender equality in higher education. More female university graduates means more women qualified for leadership positions, not just in higher ed but also in the corporate world, nonprofit organizations, the financial sector, and other centers of power traditionally dominated by men.

Colleges and universities continue to promote gender equality in new and even more effective ways. One approach currently under discussion: mandatory participation in diversity and inclusion committees, along with pay equality and more generous family leave. Many community colleges are adopting rigorous internal auditing and a commitment to living in alignment with inclusive values with great success.

Recently higher education has seen pushback against gender equality from the demographic who, due to exclusionary policies, once dominated institutions of higher education — white men. For example, in September 2020, President Donald J. Trump issued a retaliatory executive order banning mentions of racial and gender bias at institutions that receive federal funding, essentially shutting down colleges’ and universities’ ability to offer diversity and inclusion training.

In a similar move months before, Trump’s secretary of education Betsy DeVos rolled back certain Title IX protections for victims of sexual assault, a follow-up to her 2017 rollback of Title IX protections for transgender students. Clearly, gender equality is still a divisive issue, and college campuses remain flashpoints for political and ideological conflict.

The Future of Women in Higher Education Leadership

Though women’s representation at the top of higher education leadership for elite four-year research institutions has yet to catch up to men’s, it’s only a matter of time. With student body demographics at colleges and universities becoming ever more diverse, recruiting women, particularly Black women and other women of color, into senior administration roles will be a priority going forward. In the near future, expect to see a reflection of the trend that led to women becoming the majority of college graduates continuing to play out for women in higher education leadership.

Infographic Sources