Social Issues in Healthcare: Key Policies and Challenges

Tables of Contents

- What Do We Mean by Social Issues in Healthcare?

- How Are Social Factors Affecting Access to Healthcare in the U.S.?

- How Health Policy Issues Shape Our Healthcare Experience

- Real-Time Social Issues in Healthcare: COVID-19, Racism, and Other Current Epidemiology Issues

- Hospital Mortality Rates: End-of-Life Social Issues in Healthcare

- Future Social Issues in Healthcare

As soon as we enter this world, society begins to shape our lives. Social issues in healthcare influence every aspect of our well-being, from our physical and mental health to the treatment we receive from doctors. We cannot escape the values of society, nor histories of oppression and subjugation, even when we are simply seeking care for our bodies and minds.

Nowhere is the tragic reality of how social issues in healthcare affect our lives better represented than in statistics on infant mortality. Death is three times more likely for Black infants in the U.S. than for white infants if their care is administered by white doctors, according to a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Yet, if Black infants are cared for by Black doctors, their mortality rates drop by up to 58%. In healthcare as elsewhere, institutionalized racism has grim consequences.

Continue reading to learn more about social issues in healthcare — what they are, how they affect access, where they intersect with current issues in epidemiology, and how they impact hospital mortality rates.

What Do We Mean by Social Issues in Healthcare?

Social issues in healthcare are also known as social determinants of health. Social determinants of health are the circumstances of the places where people reside, work, learn, and engage in recreation. These circumstances are the result of the distribution of money, resources, and power across international, national, and regional levels. Systemic health inequities can often be attributed to social issues.

In this article, we will use the term social issues in healthcare to mean the circumstances in which people live, work, learn, and play. The sociocultural categories applied to people and their circumstances will be referred to as social factors.

Moving forward, we will delve into how access to healthcare, different epidemiology issues, and hospital mortality rates interact with these six social factors:

- Class/income

- Legal status

- Race and ethnicity

- Gender identity and sexual orientation

- Disability

- Region

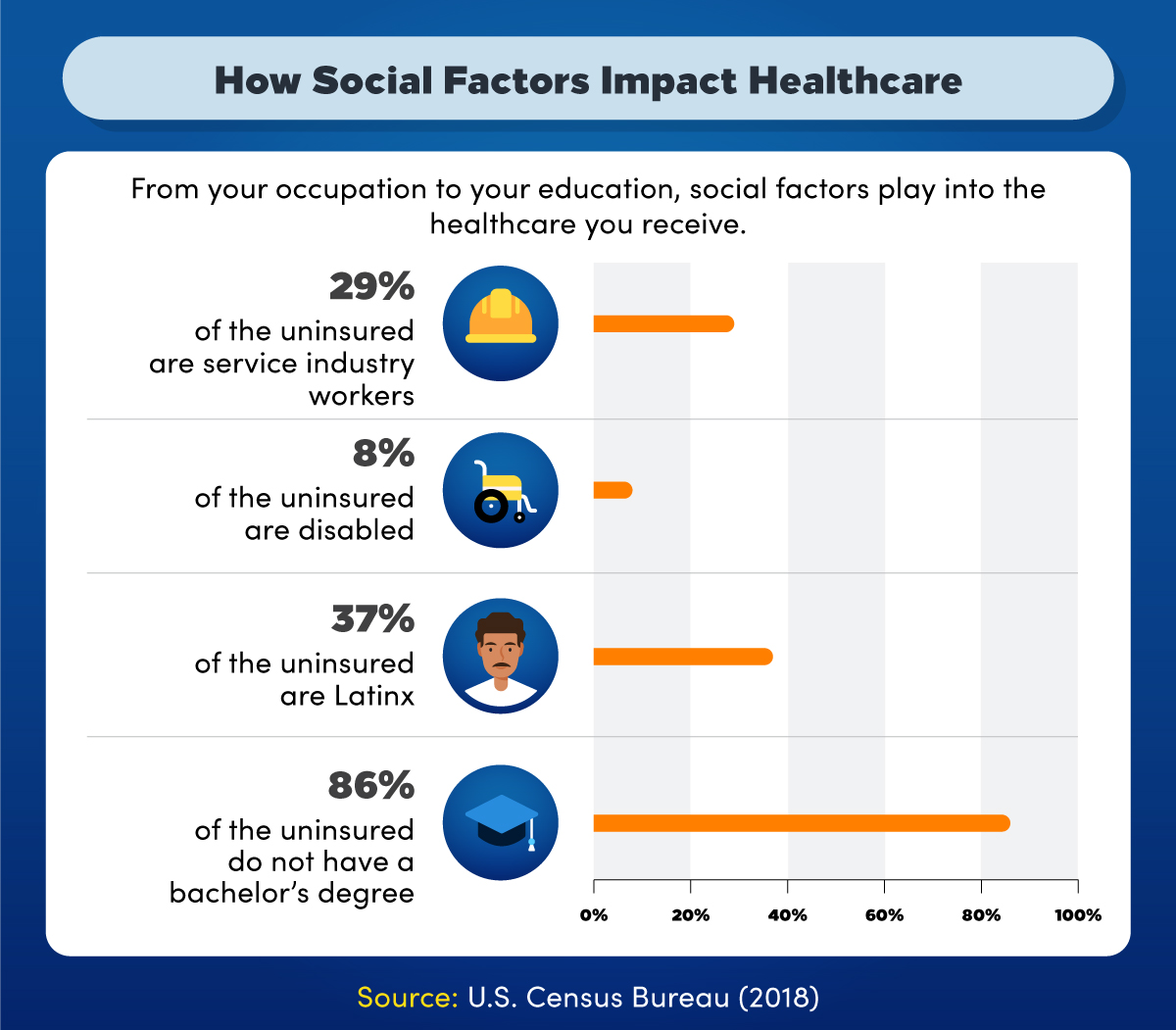

From your occupation to your education, social factors play into the healthcare you receive. According to 2018 data from the U.S. Census Bureau, 29% of the uninsured are service industry workers, 8% are disabled, 37% are Latino, and 86% of the uninsured do not have a bachelor’s degree.

How Are Social Factors Affecting Access to Healthcare in the U.S.?

Having access to healthcare means an individual can see a doctor or other healthcare provider on a regular and timely basis to achieve optimal personal health. This requires that a person gain entry to the healthcare system, that providers are nearby, and that those providers are a good fit for the person in terms of culture and personality. All of these social factors can impede a person’s ability to access healthcare.

Class and Income

Healthcare in the U.S. is inextricably linked to health insurance. An individual’s ability to obtain health insurance can vary depending on their income and employment status. In 2010 the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded the Medicaid program, which provides income to low- and no-income Americans. However, 27.9 million people remained uninsured as of 2019, most of them low-income workers, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Even with insurance, cost is a major obstacle to accessing healthcare for poor and working-class people in the U.S. Some put off needed medical care because they cannot afford a copay or deductible, and medical debt is a frequent cause of bankruptcy.

Region

Where you reside can determine whether you have access to care. In the U.S., states that have refused to expand Medicaid have higher average rates of uninsured people than states that expanded Medicaid — 11.14% of people are uninsured on average in states that did not expand Medicaid compared to 6.95% in states that did, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau analyzed by WalletHub. Yet, for residents of many other countries in the world, universal coverage is a given.

Finding a provider can be difficult in rural areas, but urban areas, particularly large cities with predominantly Black and populations, also face healthcare provider scarcities. When providers are scarce, people must go with what is available, even when those options aren’t personally or culturally compatible. If a person doesn’t feel comfortable with their doctor, they might be reluctant to seek care.

Legal Status

Noncitizens face obstacles to getting public insurance coverage, such as waiting periods, and undocumented immigrants are ineligible for most forms of public health insurance. Most employer-based coverage is also inaccessible to undocumented immigrants since employment in the U.S. typically requires a Social Security number or other proof of legal residence.

When undocumented immigrants can access healthcare services, the threat of immigration enforcement can be a deterrent to getting regular care. In a recent survey, close to half of undocumented immigrants admitted to delaying a doctor visit because they were concerned about possible deportation.

Race and Ethnicity

As the infant mortality statistics in the introduction reminds us, the U.S. has a problem with anti-Black racism, and racism in general. That race and ethnicity can present obstacles to healthcare access should, therefore, not be surprising.

Black, Latino, and Native Americans are underrepresented in medical fields, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, which means patients of those racial and ethnic backgrounds are less likely to find providers who share their race. Due to historical inequities, such as housing discrimination, Black and Native Americans are also less likely to live in areas where medical providers are plentiful.

When they can see healthcare providers, studies have shown that Black Americans’ concerns are often not taken seriously; for example, their symptoms are dismissed and their pain is minimized. Combined with the medical profession’s history of unethical experimentation on Black patients, many Black Americans find themselves waiting to see a doctor until it is too late.

Systemic racism itself has impacts on Black people and other nonwhite Americans that make their access to healthcare even worse. Nonwhite Americans are affected not only by the structural inequities that result from racist policies, but by the stress of perceived racial or ethnic bias as well. This stress can increase their risk for preventable diseases such as cancer and diabetes.

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation and gender identity are two other important factors affecting access to healthcare. Health services such as abortion, PrEP (preexposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection), and gender confirmation surgery are often politically contentious.

This has real impacts on the lives of both cisgender and and LGBTQIA people in general. The federal government recently rolled back protections that assured transgender individuals the same access to healthcare afforded to cisgender individuals, and the legal right to abortion continues to be contested in the courts. Shame and judgment also make it hard for some transgender and LGBTQIA people to find a healthcare provider they feel comfortable with.

Disability

The Americans with Disabilities Act celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. Among other things, the act mandates reasonable accommodations for disabled people to access public spaces, including medical offices and workplaces. Some disabled people have been able to work and obtain health insurance because of its passage.

Disabled people who cannot work and who receive assistance such as Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) or Supplemental Security Insurance (SSI) are eligible for Medicaid. However, some government administrations seek to curtail the breadth of federally funded healthcare coverage in ways that could impact disability benefits, such as the efforts of the Trump administration to reduce the scope of Medicaid by issuing work requirement waivers to states.

How Health Policy Issues Shape Our Healthcare Experience

Healthcare policy is created with the input of the healthcare industry, private employers, healthcare unions, and, to some extent, healthcare consumers. Health policy issues typically arise when the interests of one of these groups are over- or under-represented at the policymaking table.

A number of health policy issues are at play in the U.S. today, and they have tangible effects on the frequency and quality of our healthcare.

Currently, the U.S. is in a heated political and moral debate over the role of healthcare. Should it be a privilege or a right? The ACA was a health policy based on the idea that healthcare should more or less be a right, at least for a majority of working citizens and legal residents. Some feel the act did not go far enough, and they may support new policy proposals such as “Medicare for All.” Those who believe it went too far may want to roll back some of its protections.

Health policy issues have shaped the course of the COVID-19 pandemic as well. Some have argued that the U.S. government downplayed the severity of the outbreak in the beginning, leading to poor preparation and outcomes. The impacts of racist healthcare policies are also starkly evident in deaths associated with the pandemic: statistics, including data from the Brookings Institute, have shown that Black Americans are more likely to die from COVID-19 than other Americans.

Another example of how health policy shapes our experience of care can be found in drug pricing. From 2011 to 2016, Mylan increased the price of EpiPen, an epinephrine injector that prevents fatal anaphylaxis, by 400%, according to GoodRx. Many families were hit with a shocking bill for a necessary drug, with no options to replace it. Similar cost increases have occurred with insulin, chemotherapy drugs, and other generics.

Healthcare pricing in general will remain a key challenge for the healthcare field going into 2021. The U.S. pays more for healthcare than other rich nations, but the benefit of that expensive care is debatable. While Americans visit specialists and have diagnostic exams such as MRIs performed more often than citizens in other high-income countries, life expectancy is lower in the U.S.

Resources: Healthcare Policy Around the World

World Health Organization — Explore the legal side of healthcare around the world

HowStuffWorks — An overview of healthcare systems in 10 different countries

HealthyPeople.gov — A snapshot of global health

World101 — Different models for healthcare from around the globe

Real-Time Social Issues in Healthcare: COVID-19, Racism, and Other Current Epidemiology Issues

In simple terms, epidemiology is the study of health-related events and states (such as disease) and the conditions that lead to them in populations. Epidemiologists do not treat or diagnose disease in individuals; rather, they look at the distribution and determinants of health.

Think of epidemiologists as detectives, following a deductive process to discover the causes of disease and other adverse health events. They might ask questions such as:

- Which individuals are sick?

- What is their symptom set?

- When did their sickness begin?

- Where might they have been exposed?

- What social groups do those individuals belong to?

- What are the social determinants of health that might impact the health of those groups?

With the answers to these questions, epidemiologists can work toward determining the origin and mechanism of an infectious outbreak or other public health threat. Epidemiologists care about social issues in healthcare because they can impact the distribution of health-related events. Many current epidemiology issues intersect with social factors.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

Epidemiologists are interested in predicting where COVID-19 outbreaks are likely to occur and in what environments. Using data from testing and contact tracing, they learn about important characteristics of the virus, such as how long it typically lasts and how contagious it is. Their findings inform guidance to states and industries regarding safe reopening procedures.

Disparities in infections and deaths from COVID-19 are of concern to epidemiologists. The fact that Black and Latino Americans are dying at much higher rates than white Americans is important because it means many members of these social groups have pervasive underlying conditions that affect their health status. An effective prevention campaign must take those conditions into account.

The Opioid Epidemic

Pharmaceutical industry sales strategies in the 1990s and early 2000s led to an explosion of opioid prescriptions into the mid-2010s. The result has been a substantial increase in the number of people addicted to legal and illegal opioids such as OxyContin and heroin. Abuse of these drugs can lead to long-term disability and death. In fact, 130 people died every day in 2018 and 2019 from an opioid overdose, and many of those people came from working-class and low-income backgrounds, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Epidemiologists look at the effects of government health policies on opioid overdoses and research ways to enhance monitoring of opioid morbidity and mortality. They also study whether improved access to interventions such as naloxone and drug treatment programs has a meaningful impact on outcomes, often working together with experts in other disciplines such as psychology.

Racism and Police Brutality

Police brutality is also a current epidemiological issue. When examining the cause of injuries and deaths at the hands of police officers, epidemiologists would ask the same questions they ask when investigating disease outbreaks. Who are the victims? Black Americans are nearly three times more likely to die during an encounter with a police officer than white Americans, according to a study published in the American Journal of Public Health. What are the symptoms? Are police activities motivated by bias, such as racial profiling or excessive surveillance of nonwhite communities? Racism and police reform are major challenges epidemiology must confront going into 2021.

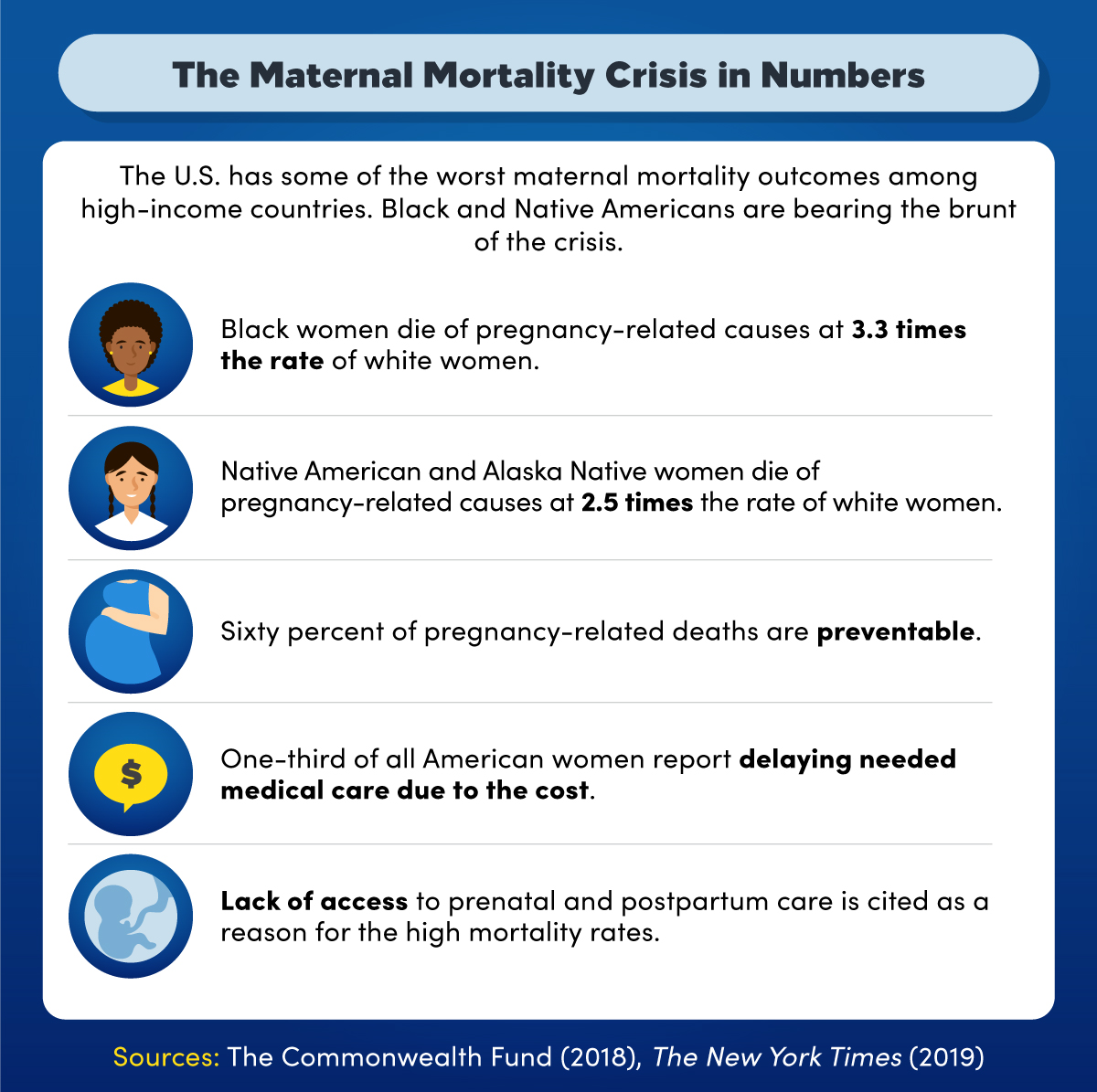

The U.S. has some of the worst maternal mortality outcomes among high-income countries. Black and Native Americans are bearing the brunt of the crisis. According to 2018 and 2019 information compiled by The Commonwealth Fund and The New York Times. Black women die of pregnancy-related causes at 3.3 times the rate of white women, and for Native American and Alaska Native women, it’s 2.5 times. In addition, 60% of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable; one-third of all American women report delaying needed medical care due to cost, and a lack of access to prenatal care and postpartum care is cited as a reason for the high mortality rates.

Hospital Mortality Rates: End-of-Life Social Issues in Healthcare

The social factors affecting access to healthcare also impact access to beginning and end-of-life care. Maternal mortality rates in the U.S. are worse than in any other rich nation, and the impacts of the crisis are not distributed evenly: Black, Native American, and Alaska Native birthing parents are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white birthing parents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A majority of all deaths related to pregnancy are preventable, and many of them result from systemic inequities in healthcare.

Hospital mortality rates in general are highly influenced by social factors. Well-funded hospitals with well-trained staff who have experience working with a variety of patients will have lower rates of death. Metropolitan areas are likely to have large surgical centers and university medical facilities with world-class specialists and state-of-the-art equipment. These areas have seen their hospital mortality rates improve over the last decade, whereas in rural areas, rates have remained flat.

For the Black community, hospital mortality rates are impacted by their experiences with the medical field over the centuries. Historical traumas such as the Tuskegee study that researched syphilis in Black men without their consent and the theft of Henrietta Lacks’ DNA have created a mistrust for the healthcare industry. Despite being more likely to live near high-quality medical facilities,

The same mistrust that keeps Black Americans from seeking care at predominantly white facilities may also lead to dissatisfactory care at the end of their lives. Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to die in the hospital, rather than at home with their families in hospice care, according to information compiled by the Center for Health Journalism. Poor communication between healthcare providers and their Black patients is cited as one potential source of this continuing disparity in end-of-life care.

Future Social Issues in Healthcare

For the next few years, COVID-19 will reverberate through our societies even after an effective treatment or vaccine is developed. We will need armies of trauma-informed providers to deal with its aftermath. Climate change will also continue to have harmful implications for our mental health as well as our physical health.

Remedying structural inequities is no small task, yet all evidence indicates it is one that must be taken on immediately if many of the crises facing the healthcare field are to be overcome.

Our fast-paced world will surely continue to generate challenges for the healthcare field to contend with, but our shared future must be anti-racist and equitable. As long as human societies rely on hierarchies of privilege and power, the same old social issues will shape our health and our care far into the future.