Writing for the Screen: How to Write a Movie Screenplay

Tables of Contents

- What Is a Screenplay?

- A Look at the Common Screenplay Format

- Examples of Effective Screenplays

- How to Format Dialogue

- What Are Some Common Screenplay Writing Techniques?

- How to Become a Screenplay Writer: A Step-by-Step Process

What ambitious professional writer has not fantasized about seeing his or her name in huge, shining letters on-screen during a film’s credit sequence: Written by [insert your name here]?

Before that can happen, though, a writer must learn how to write a movie screenplay.

Screenwriting has long been considered a “glamour” position among wordsmiths. Since the early 20th century, when silent movies began to emerge as popular entertainment, writers have played an integral role in the creation of cogent, compelling stories.

If movies are dreams brought to life on cellulose and screen, someone must channel those fantasies in a practical way. After all, the actors need to know their lines.

The set designer needs to know what the setting should look like. The production crew needs to know where to point the camera. The editors need to know how to order the scenes to tell the story.

It is the responsibility of the screenwriter to know how to translate the vision of the story into the technical language of moviemaking.

This article serves as an introduction to that process. It explores the various elements of screenwriting, such as the importance of economy of dialogue, and the relationship between character development and context.

It also introduces the characteristics that distinguish screenwriting from other forms of writing, including the strict guidelines for structure and formatting.

Finally, the article examines how writing a screenplay can teach key lessons about the craft and business of writing, complete with tips on how to build a career as a screenwriter.

What Is a Screenplay?

According to Merriam-Webster, a screenplay is “the script and often shooting directions of a story prepared for motion-picture production.” The distinction often is made between a script, which is written for stage production, and a screenplay, which is written specifically for film production.

Screenplays can be used to tell original stories or to adapt existing stories for a feature film or TV show.

Today’s screenplays include story elements such as settings, character descriptions, descriptions of actions, dialogue, and specific instructions for production such as lighting, camera angles, scene transitions, and more.

When done right, a screenplay is simultaneously a set of instructions and a distinct work of art.

The History of Screenplays

When film began to be used for public storytelling in the late 19th century, screenplays were known as scenarios. These were loose outlines of stories, which typically were only one or two minutes long and — because the films did not have sound — included virtually no dialogue.

Although scripts written for the stage and scripts written for film shared many similarities, the lack of sound for films was an obvious key difference between the two genres.

Screenplays evolved in the early 20th century as filmmaking technology advanced and demand for movies increased. Communities across the United States responded to the early movie boom by opening theaters — more than 10,000 were in operation by 1910, according to an article published by The Script Lab, “The History of the Screenplay.”

Screenwriting remains a vital pillar of the $50 billion film industry — as well as a dreamer’s longshot avenue into the movie business. What often separates the dreamers from the professionals is insider knowledge of the essentials of how to write a screenplay.

Balancing Dialogue and Description

One of the most important technical features of a screenplay is the interplay the writer establishes between description and dialogue.

Description is used to establish a setting within a scene and to convey the actions of the characters. Dialogue is defined as speech or revealed thought (known as internal dialogue) and is used to:

- Establish character

- Build conflict and drama

- Provide subtext or misdirection

- Convey emotion

- Reveal motivation

- Advance the plot

A rule for dialogue is to avoid having characters simply “shoot the breeze” when they talk, according to an article published by Script Reader Pro, “Script Dialogue Should Be More Than ‘Just Talking.’”

Rather, dialogue should consist of words that are “hard to say or hard to hear.” In other words, dialogue should be used economically to put a character under some form of pressure or into conflict.

As important as it is to employ dialogue with a purpose, writer Lauren McGrail of Lights Film School emphasizes the need for a believable world in her article “4 Examples of Good Visual Writing in a Movie Script.” According to McGrail, “Dialogue must exist in a world so real that it has its own beating heart, capturing the reader.”

Screenplay Structures and Length

During the heyday of the Hollywood studio period, when cost-efficiency became the driving force in screenwriting, standardized structures and lengths were established to create efficiency and to dictate how much film would be needed to complete the shoot.

Even though the system has changed and most movies use digital recording as opposed to film, these standards remain in place today.

In general, a screenplay should be 90 to 120 pages. The number of pages corresponds to the length of the movie: A comedy (90 pages) is around 90 minutes. A drama (120 pages) is around two hours, or 120 minutes.

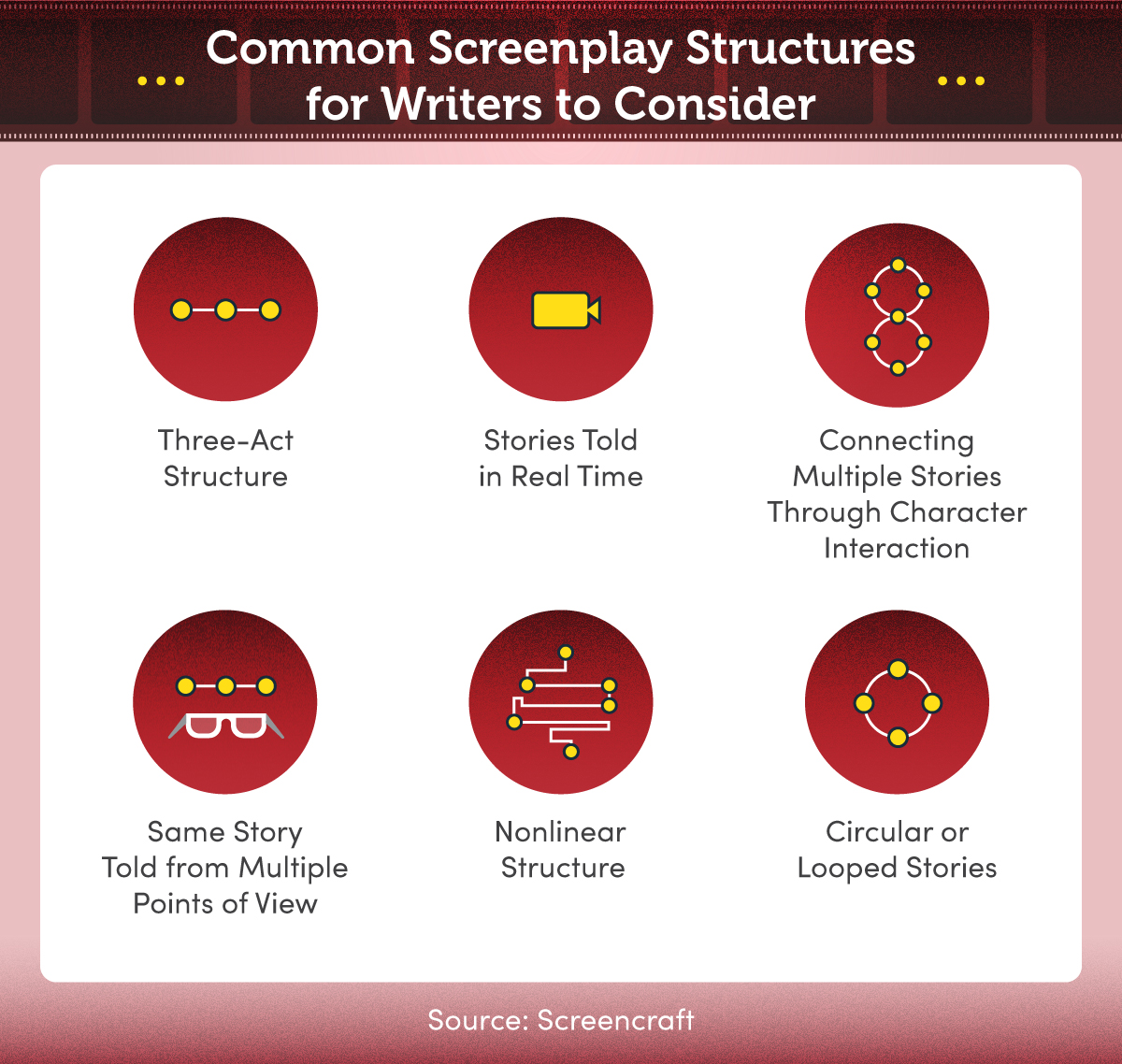

The 90- to 120-page length can take on myriad structures. The structure of a screenplay determines how the story’s plot is unveiled to the audience. Here are a few, as described in the Screencraft article “10 Screenplay Structures That Screenwriters Can Use”:

Three-Act Structure

This is the classic “beginning, middle, end” flow. It begins with a setup, moves to a confrontation, and then reveals the resolution. This is the most common structure used by screenwriters.

Real-Time Structure

The events of the story unfold in the order they occur, without scene breaks, time jumps, or flashbacks. This is also known as linear structure.

Writer’s Digest Script: Meet the Reader – Linear Equations

Multiple Timeline Structure

A number of related storylines are intertwined — but remain separate — as the “big picture” of the main story unfolds. This format may also be referred to as non-linear structure.

Fabula/Syuzhet Structure

A narrator (sometimes with an unreliable point of view) is used to tell a portion of a story, while the rest of the narrative plays out on-screen. The “fabula” is the on-screen action; the “syuzhet” is the overlaid narration.

A Look at the Common Screenplay Format

Screenplays are written to fit a rigid format. This is because a screenplay is designed to be as clear as possible for fast reading. Details as granular as font type and page size are part of the screenwriting standards practiced by established professionals and savvy newcomers alike.

Using the standard format tells the reader that the screenwriter knows the industry and respects the reader’s time. Failing to use the standard format runs the risk of a busy reader dismissing a screenplay out of hand.

Components of a Formatted Screenplay

Most screenplays are written using Courier 12-point font and printed on 8 1/2-by-11-inch bright white three-hole-punched paper. The top and bottom margins are 1 inch. The left margin is 1 1/2 inches for nondialogue and 3.7 inches from the left for dialogue blocks.

The title page should include only the title of the work, followed by the words “Written by” and the author’s name. If necessary, contact information can be included at the bottom left or bottom right of the title page.

Here are the basic elements of a formatted screenplay, as listed in the Screencraft article “Elements of Screenplay Formatting”:

- Scene heading — a brief description that denotes the scene number, the setting as interior (INT) or exterior (EXT), the location, and whether it takes place during the DAY or at NIGHT

- Action — a detailed description of what the characters are doing in the scene; also might include instructions for the camera crew, sound crew, and other members of the production team

- Character name (dialogue) — the name of the character in all capital letters, centered on the page above the spoken dialogue

- Parentheticals (extensions) — words that describe the dialogue context in parentheses under the character’s name, often a description of the tone of voice or gestures used by the character for a line of dialogue

- Dialogue — words spoken by the character, printed as a block under the character’s name, and any parentheticals

- Transition — if needed, editorial direction for cutting from the current scene to the next (example: FADE OUT)

For clarity, the word MORE or the abbreviation CONT’D can be used at the bottom of a page to show that the scene continues on the next page. The word END can be used at the bottom of the final page.

- Script Reader Pro: How to Format Dialogue in a Screenplay

- Writer’s Digest Script: Why is Proper Script Writing Format Important?

- Screencraft: Elements of Screenplay Formatting

Using Screenplay Formatting Software

While a writer can format her or his own screenplay manually, the process also can be automated using screenplay formatting software such as Final Draft or Scrivener. Most of the established leaders in the software field require payment, but some also offer scaled-down free versions.

A screenplay formatting program might provide page templates for the title page, scene, description, dialogue, and more. For instance, the simplest function of a program such as Final Draft allows a writer to plug in the words and automatically save them in professional screenplay format. The more advanced programs provide writing prompts, character names, and backgrounds, serving as a digital writing coach.

- Indie Film Hustle: 5 Apps Better & Cheaper than Final Draft

- Studio Binder: 9 Best Screenwriting Software Tools to Use in 2020

- Careers In Film: Best Screenwriting Software 2020

Examples of Effective Screenplays

A good place to start an exploration of examples of effective screenplays is the historical list of Academy Award-winning screenplays. One of the most renowned films in American history — Citizen Kane — also happens to have one of the most riveting and artful screenplays in American letters.

It was written by Orson Welles, who also directed and starred in the 1941 biopic loosely based on the life of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. Welles and fellow screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz won the Oscar in 1942 for Best Original Screenplay, and Citizen Kane was named the No. 1 American movie of all time by the American Film Institute in 2007.

One of the most influential adapted screenplays was the film version of the novel The Godfather, by author Mario Puzo and filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola. Puzo and Coppola shared the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay.

What these famous examples of effective screenplays shared was their economic use of dialogue to establish character and conflict, their clear and direct descriptions, and their ability to draw a reader in early and maintain the narrative momentum on every page.

Visual Description in a Screenplay

The prologue for Citizen Kane stands on its own as a literary achievement. Here is a sample of the sparse yet vivid visual description that was used to create one of the most memorable movie openings in cinematic history:

INT. KANE’S BEDROOM — FAINT DAWN — SNOW SCENE.

An incredible one. Big, impossible flakes of snow, a too picturesque farmhouse and a snow man. The jingling of sleigh bells in the musical score now makes an ironic reference to Indian Temple bells — the music freezes —

KANE’S OLD OLD VOICE

Rosebud…

The camera pulls back, showing the whole scene to be contained in one of those glass balls which are sold in novelty stores all over the world. A hand — Kane’s hand, which has been holding the ball, relaxes. The ball falls out of his hand and bounds down two carpeted steps leading to the bed, the camera following. The ball falls off the last step onto the marble floor where it breaks, the fragments glittering in the first rays of the morning sun. This ray cuts an angular pattern across the floor, suddenly crossed with a thousand bars of light as the blinds are pulled across the window.

The writers used description to establish the setting (the bedroom) and mood (dark, foreboding). They then used a shift in the point of view of the camera to further establish the state of mind of the dying Kane and to introduce the enduring image of the shattering glass ball and the glittering shards to set up a scene transition. They did all of that with 162 words, only one of which was spoken — although it has since become one of the most famous pieces of dialogue in film history: “Rosebud.”

- Lights Film School: 4 Examples of Good Visual Writing in a Movie Script

- Screenplay: How to Incorporate Visuals into Your Screenplay

- Writer’s Digest Script: Welcome to the Visual Mindscape of the Screenplay

Effective Parenthetical Screen Descriptions

In the screenplay for the Academy Award-winning film The King’s Speech (Best Original Screenplay, 2010), writer David Seidler provided an excellent example of how to use parenthetical description to simplify the reading process:

EXT. ROYAL PODIUM — DAY

Bertie is frozen at the microphone. His neck and jaw muscles contract and quiver.

BERTIE

I have received from his Majesty the K … K

[For ease of reading, Bertie’s stammer will not be indicated from this point in the script.]

The stammer careens back at him, amplified and distorted by the stadium PA system.

Here, the writer spelled out the initial stammer that bedeviled the character and drove the plot throughout the film. Later in the script, the writer used parenthetical description to alert the actor that it was time to speak with a stammer. Seidler also indicated the severity of the stammer in each case.

How to Format Dialogue

As mentioned earlier, dialogue serves many important purposes in a screenplay. It can drive the plot, establish a character’s point of view, set up conflict, mislead the audience intentionally, and achieve many other functions within a successful narrative.

The Script Reader Pro article “Script Dialogue Should Be More Than ‘Just Talking,’” provides a number of checklists to assure that the dialogue is doing its job within the screenplay. The questions the article suggests asking about a scripted conversation include:

- Is the conversation difficult for one or both of the characters?

- Does the conversation deserve to be in the script?

- Does the dialogue amuse, interest, or shock you?

- Does the conversation feel or sound natural?

- Has the narrative shifted in any way by the end of the conversation?

Dialogue must be presented in the proper format to be as effective as possible. Confusing or unclear dialogue slows down the reading process and can be unsettling for the actors. Formatting during the writing process helps the writer make sure that he or she has presented the spoken words as clearly as possible and that each line of dialogue accomplishes its purpose.

Visual Markers of Dialogue

Most dialogue is written as a single block underneath the name of the person speaking. One-screen conversations are denoted in this way.

Minor, unnamed characters who speak should be referred to in the script by their role: CLERK #1 or ATTENDANT #2. The way these minor characters are referred to must be consistent throughout the screenplay to avoid confusion.

Other dialogue might be spoken off-screen as a voice-over, as with a narrator. In these cases, the spoken words are marked with the abbreviation for voice-over in parentheses: (V.O.).

Off-screen dialogue spoken by characters, as opposed to a narrator, should be marked accordingly: (O.S.). This can be used to denote a character in another part of a room, such as when the facial expression of one character is relevant as another is talking.

Another formatting guideline is to keep parenthetical directions as simple as possible. Insert them in parentheses under the character’s name. Do not use capital letters or end punctuation.

Formatting Unusual Dialogue Types

Human speech rarely follows the written pattern exactly. People speak hesitatingly, or quickly, or quietly, or with a lisp. In conversation, people often let sentences trail off, or interrupt, or speak over one another.

These quirks of speech should be formatted within the screenplay to give the reader a clear idea of not only what the character is saying but also how the dialogue is supposed to sound.

For example, some people speak to each other simultaneously. This is called dual dialogue, or cross talk. It can be formatted by placing the characters’ dialogue blocks side by side, or by inserting a parenthetical direction that tells both characters to talk at once.

If a character is speaking by phone, or using another digital device, the dialogue should be marked with a brief parenthetical: (over phone) or (over walkie-talkie).

What Are Some Common Screenplay Writing Techniques?

-Outline the Screenplay’s Story Structure

-Write Dialogue with Purpose

-Write Complex Characters with Defined Character Arcs

-Express Character Emotion Through Intentional Action

Source: Writer’s Digest

One of the most influential thinkers in screenwriting never earned a screen credit. Joseph Campbell, a professor of comparative religion and mythology, cut the path for screenwriters such as George Lucas (Star Wars) by authoring the book The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

In his analysis of mythological and cosmological thinking, Campbell laid out the hero’s adventure, a journey of departure, experience, and return. It was, Campbell said, the one story told many times over the centuries.

The pattern of the hero’s adventure can be identified time and again in films and novels. It is the basic building block for storytelling — a hero sacrifices something, thereby changing herself or himself and, in doing so, changing the world.

With the hero’s adventure as a starting point, a screenwriter can dive into the work. Yet, no pattern or formula will suffice if the goal is to capture the attention of a movie-going audience. A connection must be made, and quickly.

There are a number of common screenplay techniques writers use to capture attention and propel a narrative from start to finish. The Screencraft article “10 Most Basic Things to Remember Before Starting a Screenplay” provides sound guidance in these techniques, including the importance of a compelling opening, when and how to fill in the blanks of character development, and how to create conflict that demands resolution.

- Writer’s Digest: 10 Screenwriting Techniques Every Writer Can Employ

- Screencraft: 10 Most Basic Things to Remember Before Starting a Screenplay

- Studio Binder: Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey: A Better Screenplay in 17 Steps

Importance of the Writer’s Attitude and Mindset

In discussing attitude and mindset, we should start with a pause at the ideal stopping point: the end of the first draft. Once a screenplay’s bones have been filled out, once every scene is on paper or a computer screen, once every transition is set, once every conflict is seemingly resolved, the writer should distance herself from the work. Take time to reset the mind.

Writing a screenplay is a huge commitment of time, emotion, and brainpower. It is an investment of creativity and energy. With the first draft finished, the writer is free to turn his attention to other things — for a while.

Eventually, with the mind and body recharged, the writer must return to the work and look at it with fresh eyes. Only when a bit of distance has been established can the writer approach the revision process with the right mindset and attitude.

Developing Character Complexity and Goals

To develop complex, believable characters, the writer must give the character goals.

Conflict is plot. Without conflict, there is no story. Without complex characters, there is no conflict. Identify early in the script what a character needs or wants — this is the catalyst for conflict. Once the desire is identified, create obstacles for the character to overcome. This is the building block of every story.

The hero’s adventure is built on the actions associated with the hero overcoming obstacles to reach a goal. The hero might fall short of the goal, or reach it but then lose something else important, and this creates even more emotional complexity.

Balancing a Character’s Actions and Goals

The writer should take care not to make it too easy for the character to achieve conflict resolution. A simple solution robs the audience of suspense and reduces the level of satisfaction once the goal is reached.

One of Campbell’s milestones on the hero’s journey is the introduction of a guide, or supernatural aid. The guide is meant to help the character discover personal characteristics that allow the hero to move on to the next stage of the journey.

The aid the character receives along the way should not ease the path too much. The writer must establish a balance between what the guide can provide and what the character needs to reach the final goal. Ultimately, the character must progress beyond the guide’s ability to provide assistance — thereby forcing the hero to face the journey alone.

How to Become a Screenplay Writer: A Step-by-Step Process

Based on the advice found in a library of contemporary articles that describe how to become a screenwriter, one of the key personal qualities a writer needs is luck. “Becoming a screenplay writer is an exciting gamble,” begins an article in the Houston Chronicle, “Steps to Becoming a Scriptwriter.”

To be sure, there are steps a writer can take to improve his or her odds of landing that dream job in screenwriting. In addition to luck, a writer will need to be patient and spend a lot of time writing, reading, watching movies, and talking to people in the film industry.

Writing Skills, Interpersonal Competency, Creativity

According to an article in The Guardian, “An Insider’s Guide to Becoming a Screenwriter,” a prospective screenwriter will be judged “primarily on the quality of the creative work you generate.” Before you embark on a potential career in screenwriting, make sure you possess the creative spark necessary to develop compelling stories for the screen.

If you believe you have the right creative drive, you will need to examine your interpersonal skills and emotional intelligence. Do you have what it takes to overcome repeated rejections? Are you able to navigate the complex and sometimes frustrating world of filmmaking? If you believe the answer is yes, move on to the next step: Building a network in the industry.

Building a Network for Critiquing

Once you have begun to write screenplays, you may want to ask for a professional writer to critique the work. The people you ask to read your work should be trusted to tell you the truth about it — especially if you suspect the work falls short of your expectations. False praise is not constructive. Be sure to make it clear that you are open to constructive criticism, and don’t be afraid to ask the fundamental question, “How do I write a screenplay?”

Once you have a few screenplays in final draft form, it is time to begin sending them out. Be strategic. Few literary agents, studios, or production companies respond to screenplays received out of the blue. Reach out to your trusted editors for advice about agencies or production companies that are accepting submissions.

The two major organizations that support screenwriters, the Writers Guild of America East and Writers Guild of America West, provide guidance for employment and more.

Gaining Movie Industry Work Experience

According to The Guardian, a prospective screenwriter should expect to spend “three to five years trying to get a break” in the film industry. The author of that piece, screenwriter Stephen Davis, does not necessarily recommend “taking a backroom job” in the industry to get a foot in the door if you have a “stellar script at the ready.”

Davis admits that working for a movie producer provided him with valuable insight into the industry. Yet, the most important factor was the fact that he “was writing in the evenings and on my days off.”

Every path to a successful screenwriting career is unique, but there is one commonality: The journey is fueled by the written word. The physical act of writing — moving your fingers across a keyboard or making marks with a pen or pencil on a piece of paper — helps a screenwriter hone his or her creative ability. It helps a writer work through mistakes and find the story as it is meant to be told.

There is never a guarantee that the “big break” will happen. But those who commit to a life of writing, enjoy watching a lot of different films across genres, and make a point of learning the craft from those who do it for a living are more likely to create the opportunity to pursue the dream of becoming a professional screenwriter.

Suggested Reading

Creative Jobs for English Majors

Sources

The Guardian, An Insider’s Guide to Becoming a Screenwriter

Houston Chronicle, Steps to Becoming a Scriptwriter

Lights Film School, Lauren McGrail, 4 Examples of Good Visual Writing in a Movie Script

LitReactor, 5 Reasons Why You Should Write a Screenplay

Screencraft, Should You Be a Novelist or Screenwriter?

Screencraft, 10 Most Basic Things to Remember Before Starting a Screenplay

Screencraft, 10 Screenplay Structures That Screenwriters Can Use

Script, Why is Proper Script Writing Format Important?

Writer’s Digest, 10 Screenwriting Techniques Every Writer Can Employ

Screencraft, Exploration of the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey

Screencraft, Elements of Screenplay Formatting

Studio Binder, Matt Rickett, Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey: a Better Screenplay in 17 Steps

Studio Binder, Matt Vasiliauskas, Top Screenwriting Tips and Strategies from the Coen Brothers

Bureau of Labor Statistics, From Script to Screen: Careers in Film Production

Studio Binder, SC Lannom, How to Become a Paid Screenwriter in 2020: a Step by Step Guide

The Script Lab, Michelle Donnelly, The History of the Screenplay

Merriam-Webster, Screenplay Definition

Script Reader Pro, Script Dialogue Should be More than ‘Just Talking’